Growing up in Nigeria, Layo George watched her mother deliver countless babies in her own home and the homes of her closest friends. For much of her life, George thought she would follow in her mother’s footsteps and become a midwife. However, she decided on maternal health nursing instead. As George worked in delivery rooms, she noticed that the level of care provided to low-income parents and people of color was vastly different than the level of care provided to white parents.

She also noticed that parents of color didn’t interact with the healthcare system the same way as white parents. George’s own experience as a Black woman and an immigrant gave her all the explanation she needed — health outcomes for parents of color are significantly worse than outcomes for white parents.

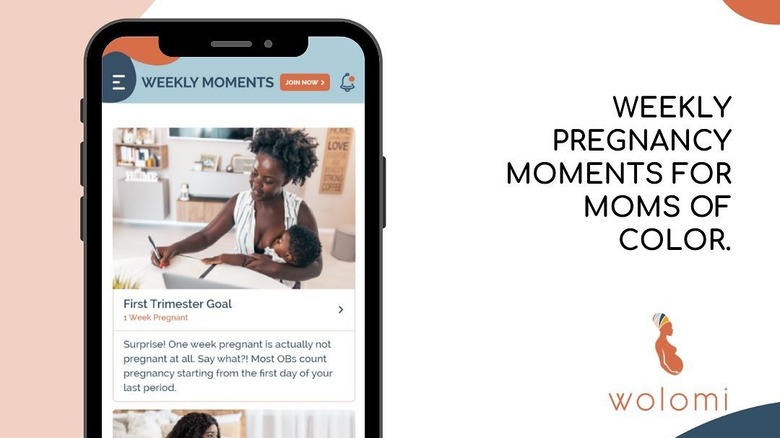

George decided that she wanted to address these issues from a different angle. She earned a degree in healthcare administration so she could bring her perspective as a Black woman to the decision makers capable of changing maternal health practices and outcomes. George also decided that she wanted to empower parents of color to make informed decisions about their care, so she created Wolomi, the first pregnancy app exclusively for parents of color.

In an exclusive interview with Health Digest, George talked about the racial disparities in maternal healthcare, her own experiences as a Black mother, and how she hopes Wolomi will help change the birthing experience for people of color.

Finding her path to maternal health

How did your career in healthcare get started?

I am a nurse. My background is as a nurse. I was trained as a registered nurse and that’s really how I got started in healthcare.

My mom was a midwife when I was growing up. I was in a position to see her do home birth — this was in Nigeria — and have it be a really joyous environment. I really thought that I was going to be a midwife, but then I realized that’s not the path for me, which is all good. I was a maternal health nurse.

I decided [afterward] that I was interested in innovation and all of those things. My path switched from that to working as an innovation nurse. From there, I learned a lot, a little bit about IT, and it transformed.

I went to get my master’s in healthcare administration because I really got into equity as the population changes. I am seeing that a lot of the patients are going to be people like me, and the people who are making the decisions about what to do in the healthcare system are not always having us at the table. I felt like, for us to achieve equity in healthcare, you need people who understand the community that’s being served. That’s how I decided getting a master’s in healthcare administration was the best route for me.

From there, I met a professor who was like, “Wow, you should really do innovation, and do a startup.”

Reworking the system for women of color

I was doing my thesis in developing maternal healthcare for women of color. What does remodeling look like? A little bit about that … When I was working as a bedside nurse, I was working in, at first, a small town in Wisconsin. I saw that the level of care that was given to the moms as far as evidence based things … [the area is a bit] rural. I don’t want to offend anybody … we have a lot of other rural towns that connect to where I live. It’s not a big town, it’s not a big city, but it’s a small town … [it was amazing,] the kind of innovation that they had! First of all, when you had the baby, you were entitled to a complimentary massage … That’s the first time that I saw that all the nurses were trained in assisting with breastfeeding. Then, you have a breastfeeding lounge with music. The labor room was overlooking a lake. It was [a bunch of] nice things.

Growing up in the District of Columbia, not really seeing a lot of that … and the pediatrician would … you could choose your pediatrician and the pediatrician will come to the hospital before you’re delivered to start the care of your kid from there. That’s not something we have in inner city America. You don’t get that kind thing, but I didn’t know. I was trained in inner city America, so I didn’t know those things. Then, my eyes opened.

When you talk about the District of Columbia or the neighborhood where we call the DMV area, it is the house to one of the most successful, income wise, Black Americans in the country. For us to not have the basic evidence-based things when you’re delivering … When I went back to the bedside, we didn’t even have a lot of baby friendly hospitals then. I was working with a nurse who was telling me that you should give water to the baby first. You’re talking about backwards [methods] and it’s like, whoa.

In the small town, in the Midwest where the income level wasn’t that high, they were getting good care, evidence based care. When you come to this inner city, the neighboring city and the neighborhood town suburbs near the inner city that have very, very high income, you have to have very high income to live in the District of Columbia. Very, very high income. I’m not even getting close.

When I started to do that research, like the disparity in outcomes, it became more obvious how this came to be. For me, it’s [all about], what life do you value? It’s a lot of … that’s how you bring evidence based [information]. How fast can you do [produce] evidence? You value that life, no matter how poor. Statistics show that no matter if you’re rich or poor, you’re still three to four times as likely as a Black woman who is pregnant to die. It makes sense. I saw it as a nurse and as a healthcare administrator. I saw the stats, doing our research. Being able to connect that dot, that’s a lot more than you asked for, but that’s what I gave you.

Bringing joy back into childbirth

You answered a lot of this already, but if you could pick one moment that made you decide “maternal health is going to be my thing that I’m focusing my work on,” [what would it be?]

That one moment, honestly, has accumulated over the years. As a young child, I saw my mom be a midwife and deliver and the joy of it. That’s one of the things we named Wolomi after … Wolomi is a short form of a Yoruba word called “Eku owolomi,” meaning “happy dipping hands in water.” It’s the community aspect of that. When you have a child, you’re always washing the baby, washing cloth diapers, cleaning the mom. Your hands … making food. Your hands are always in water. It’s the happiness of that. It’s an homage to that past of growing up with a mom who was delivering her friends in the room, a community thing to it, this joyous thing. That’s always been in the back of my mind. That’s what led me to maternal health.

I’m always interested in wellness … Unfortunately for us in the US, our health system is not very preventative. It’s more like, “We let you become bad and then we try to fix it,” because … it makes more money that way. That was how I got into maternal health, the inspiration for my mom and then my wellness, the interest in wellness.

So when I graduated from nursing school, I really didn’t want to be, I didn’t really have the heart to do like med surg [nursing] or any of those things. I wanted to incorporate some kind of wellness. So I was debating primary care and maternal health. Somewhere where people smiled! That was, I was like, “I want to be where people smile.”

Little did I know that there’s a lot of suffering that goes on in maternal health, which led me down this path. I wanted it to be where people smile, where people are happy. That’s how I ended up in maternal health. Maternal health was a natural place where, in my head, people come in there, they’re happy. They have their child. It’s a happy moment. I could be part of that moment. I then go home. Everybody’s happy.

Racial disparities in perinatal care

You’ve touched on this a little already, too, but what kind of barriers to access do women of color face when they’re looking for perinatal care?

There are a lot of things. One is that our healthcare system does not provide all the things that we need to be successful. By successful I mean, when you have — when you’re on that journey — your ability to feel supported, your ability to have all the tools that you need, your ability to make the choices that are going to lead you down a not C-section route, your ability to breastfeed appropriately, without stress, [and] your ability to have your mental health together.

One of the things that I did when I was younger, when I first started working, is I was able to observe how white women in the District of Columbia [gave birth]. One of the things was, at that time, they had a birthing center, which is now … They’ve changed their model a little bit, but they had a birthing center. Back then, this was before I decided to have kids or anything like that, I realized that a lot of the people who frequented the birthing center were white women.

It was created in the center of the city where people thought, “Okay, there will be a lot of… they’re going to be servicing Hispanic moms, Black moms, and all of that,” but that didn’t happen. They knew, somehow, the word had gotten out that midwifery is a good way to go. Mind you, back in the day, Black women were pioneers of midwifery. That’s another story, but I want to make sure I answer your question. They knew something that we didn’t know … They knew how to say, “Okay, in order to navigate the healthcare system, I know that midwifery can get good outcomes, or I know how to shop for my provider and my OB and to ask the right questions.”

They [alsso] knew that, “Okay, before I have my baby, I need to set up short term disability so I can be out for three months.” That’s the first [thing]… I was like, “If I ever told my mother back then that I could be off with my kid for three months, she would think I was [full of it].” It’s [the fact] that immigrants, no, you don’t stay off work. Somehow, I saw that they learned the importance of that. You could be most successful at breastfeeding if, guess what, if you’re not stressed about going back to work in three or whatever weeks!

The gaps in pregnancy care for parents of color

Art_Photo/Shutterstock

Back to your question, it’s almost like we, when we get pregnant, even if it’s planned, the healthcare system takes over and they tell us what to do, and then you have that baby. It’s like, “I don’t know what happened to me.” That is what’s missing.

Unfortunately, the healthcare system doesn’t always pay for the things that you need … we’re talking about learning the experiences of those people who are getting good outcomes. Granted, we’re still way behind the rest of the Western world in our outcomes, in general, but when you look at people who are getting good outcomes in that system, what they’re doing, meaning that they are finding ways outside of the healthcare system to pay for support, to get the support they need, to get the doula, to get the massage, prenatal massage, to get all of those things, they are owning their journey. It’s not like the healthcare system is owning [it] … that’s the major gap.

The first important thing is racism in the system. All of that stuff. That, for me, is going to take, God knows [how long] to fix, but there are things we can do, right? There are things that white women are doing that’s helping them to own that journey. That’s something we have to do. We have to see ourselves as a customer of the healthcare system. That’s where the big gap is. Yes, the healthcare system is racist, because structurally, that’s what it is. I’m sorry to say, I live in this skin color, and I know that. Even [with] the healthcare system, I just told you the story about the disparity … but we can make a choice.

We can make a choice not to go to that racist doctor. Not all the doctors come to work. Not all the doctors are racist. You can make a choice. You could learn how they could talk to you. You could learn how to teach them how to talk to you. You can learn how to deserve respect. I always say, you don’t go to the store to buy something and if you don’t like it, you take it home. You don’t do that! It’s the same thing with the healthcare system.

That’s the gap for us because the healthcare system doesn’t always give us what we need to have a comprehensive plan to own our pregnancy journey. We oftentimes don’t know that we can go out and get those things. You can go out and make your team. You can go out and plan for six months off work, and you’re entitled to do that. If finances are a thing, you plan ahead. That’s the major gap. If the healthcare system can pay for all of those things, it would be great, but we can’t hold our life. We still need to enjoy our journey.

Shaping her own pregnancy journey

The way I was able to overcome that gap was … even as a nurse, I was scared. I did not want to die, because I feel like I knew too much, not only [about] death, but the suffering that goes through it, not being heard, not being, feeling listened to.

I was able to go on a sabbatical when I was pregnant. Now, that [might be considered] a little too much, but I wanted to have my mind together. I got my therapy. I made sure I was in therapy. I made sure that I took a sabbatical. We went to a place near the beach. I was in school at the time, but I also left the workplace because that was a source of stress for me. I was removing all the stress because I was like, “I am birthing, I’m creating a life and I’m going to own this.”

We know this sense of stress and all of that on our body, on the effects of our outcomes. I did that, and on Thursday mornings, I would go to prenatal yoga. I would get a prenatal massage when I was able to do so. I was able to save that money. The healthcare system didn’t pay for that. I had to pay for that, but I saw other people, my coworkers who did it. You could really enjoy this journey. You could really pamper yourself.

I had an OB. I started with a midwife, then I had an OB, because I changed my city and I couldn’t get a midwife that I could work with. I went to the OB that was referred to me by the prenatal yoga person, so I created my own team. That’s how I did it, and I don’t feel … Oftentimes, you hear that things happen. With my OB, I had a conversation with her. I want to labor at home for a while because we know evidence now shows that if you’re in active labor, stay home for a while, before you get to the hospital and you get strapped up, gravity is not a thing. Then, you’re going to be C-section’d. Having those conversations with her, it was hard, but she listened because doctors are human beings.

Ut takes a lot to challenge things because they went to school for it. The thing is that we are experts in our own body, so you know what’s wrong, and you know how it feels. It’s not a disrespect, but that’s the thing: finding a doctor [to whom] you can say, “Hey, this is what I want.” One of the ways that I was able to have those conversations with my OB was I told her, “What is it that’s going to make you upset when I get to the labor room? I want to labor at home, so you give me the parameters, because I’m going to do it.” She was like, “If your membrane ruptures, make sure you don’t stay home up to three hours. That’s the only thing I want from you. I would not be ready when I see you.”

We worked it out. They’re humans and you have to; it’s like a relationship. It’s important that we have this conversation, and going back to your question about gaps, it’s important that we know that it’s a relationship. It’s an education around the health system. Education about navigating… It’s like another class that you got to take.

Disparities in postpartum care for parents of color

When we get to that postpartum stage, what barriers to access do mothers of color encounter when seeking care for mental health?

For mental health, number one… it depends. For both of them, during pregnancy and postpartum, I want to make sure that I mention that there are two separate categories. If you’re a mom, but on Medicaid, your barriers are compounded, because not all healthcare providers are going to take Medicaid. Choices are limited. Even if you don’t like your provider, unfortunately, sometimes you are stuck, especially if you have complications. There might be only one specialist that deals with it, so, you stop. That’s a barrier, what the options are for Medicaid moms.

Also for moms, especially in terms of health, is a thing like being able to travel to a certain place. In DC, there’s a lot of effort in putting health centers and stuff and things like that in areas that are health deserts and food deserts. That could be a barrier because traveling can be expensive, so [transportation] can be expensive.

When you are getting Medicaid or you’re a mom that’s needed a little help, it’s a compounded issue, because you have to deal with all of these things. Who knows what you’re dealing with at home? Who knows what the landlord situation and the infestation and all of those things that are going on?

Then, when we talk about mental health, how do you make sure that if you find a mental health therapist that you love, they might not take Medicaid? A lot of times, I pay out of pocket for insurance, for mental health therapists. Even with the private insurance, I had a provider that I really liked and she changed where she worked, and she started her own practice. She said, “You know, I don’t take most insurance.” I had to pay out of pocket. Even for me, it’s a barrier. I had to limit and budget, so it’s a barrier. Access to culturally competent mental health specialists is a barrier for all of us. It’s challenging.

Disparities in postpartum mental health care

Prostock-studio/Shutterstock

[Regarding mental health] in pregnancy, postpartum, and in postpartum screening – one of the things that we are very adamant about at Wolomi is screening. When you download the app, we screen you. There’s a standard screening we do, because we want to know how you’re doing. We want to know where to support you.

I was on the panel yesterday and we were talking about, “Yes, we do have a mental health therapist on the app to chat, but guess what? People are not going to chat with that mental therapist.” We had to find another way to make sure that people are engaging.

Our pillars … Our most important pillar is making midwifery philosophy, the idea of interdisciplinary care, accessible and also maternal mental health. That means, for us, when we are doing a pregnancy circle, one is going to be led by a mental health therapist. When they do, it’s amazing. You wouldn’t get the moms to chat voluntarily, but when it’s in a circle and the therapist is leading, there’s something about it. Finding ways to incorporate it so that it’s not a standalone thing, it’s not … Mental health is not standalone. It’s something that is incorporated in all we do.

The third aspect of the pillar for us is early childhood development. We have our community pediatrician who is very passionate about that, making sure that we are ready for … that we know what’s going on with our child to combat some of the statistics, that are horrific with Black and brown children.

That’s another thing, the effect when we are talking about birthing people of color, the effect of racism. Yes, you made it through the healthcare system and you didn’t die or you didn’t suffer, but I could not tell you how much a lot of our moms, including me, sometimes feel the pressure of when an attack happens. When an attack happens, when a child is gunned down, when a group of people is gunned down because of their race, that does something to the women who are creating those Black or brown lives … There’s a layer, and for us, that’s very crucial. How important is mental health that we are dealing with some of these things, and we are having those conversations? It’s very important.

How parents of color are treated differently in the healthcare system

How are women of color treated differently during pregnancy and their birthing experience and postpartum? What kind of things happen to women of color that don’t happen to white women?

I could even talk about my own. In general, this is what we know. Oftentimes when we — it doesn’t matter how many appointments you go to or the fact that you are voicing your concerns — you more than likely get ignored, and your concerns not taken seriously. I was listening to a webinar where they were saying, even when that concern is noticed, somehow they’re noticing a difference in intervention and how quickly — especially when you’re talking about cardiac issues in maternal health — even when a mom is reporting the symptom at the same time as a white woman, and she’s doing all the things, intervention, which we know is very crucial in cardiac issues, can be delayed.

There’s something about our system, and honestly, not a lot of providers are out here saying, “I’m going to be racist,” but there’s something in our system that makes us not value a particular life because of how they look. That is a societal problem that we all have to tackle together, because of how they look or because of their sexual orientation, who knows, there’s all of these things. We have to deal with that as a society.

I had a personal experience with this. Even though I did all the things that I wanted to do during my pregnancy journey … The part that I could not control was when we got to the ER. Sometimes when you deliver, you … who knows when you’re going to start contracting. When it was time for me to go to the hospital, it was late at night. We went there, my doula was white. She was holding a ball, a birthing ball, and my mom, my husband and I would walk into the ER. They looked at her and said, “How can I help you?” They [ignored] the woman who was in labor pain, and she was so confused by that.

That’s an example of how that happens. I controlled, I tried everything else. I knew that if I could get to my provider, she’s the one that’s going to be making the decision about my life or death. That part, I think I got. I picked a provider that I trusted, but getting to her was a problem. I wrote to the health system. I don’t know if they took it seriously or not, but I filled out that survey.

When the doula and I, afterwards when we had a baby and all that, we were debriefing. She was like, “I don’t know what happened in there, at the ER. That was weird. Right?”

I was like, “No, that’s racism. It’s not weirdness, it’s racism. They thought your life is worth more than me. I’m in pain, and they thought you needed to … We came in together, they turned to you and asked you, and you had to point to me, the woman who was in pain at the ER, not the woman who was walking in with a … Anyway. I don’t know how we got there.

It’s a perfect illustration of what I asked, which was how women of color get treated differently. The fact that people are so oblivious to [the fact that] this happens all the time for women of color who are having a birthing experience.

Yeah, and with my doulas, I was probably the first Black client she had. Who knows. She couldn’t articulate what that was. She knew it was wrong. It was weird, but racism is the last thing a lot of people want to say. If you’re the one that’s receiving it, it’s the first or second thing.

Creating a safe community for people of color

You started to talk a little bit about Wolomi, but can you tell us how that came to your mind, how you decided to start it?

Wolomi started because of all of these things. I really wanted women to own their journey. I wanted us to own our journey and take the power a little bit away from the health system, and be able to shop around. We started with a walk-in group and the walk-in group started and people didn’t show up. In surveying the moms and asking them questions and talking to them, I realized they wanted to be with other moms on that journey.

Then, we had an event that had our pediatrician and me talking at a restaurant. It was great. That was really one of our first events. We started to think about, “How do we create a joyous thing where we can also sprinkle a little bit of healthcare into it?” When we had that event, moms didn’t want to leave. They kept having conversations and all that.

We moved from that to a WhatsApp group, and then the WhatsApp group developed into, “Okay, we need to develop another platform where people can actually, who just joined us, can go back and read the conversations we’ve had so that they could learn from it.” To be sustainable, we had to actually have a business model. That’s our journey.

The Wolomi community

What were you looking to kind of bring to the community with Wolomi?

We are bringing a safe space where moms can feel validated, where they can feel joyful on their journey, that they can feel validated and they can feel like they have the tools to navigate the healthcare system. Oftentimes, moms come to the platform and they’re like, “I just had this conversation with this doctor, but I feel this way.” We help them take a step back and really figure out the words to use to get the things that you want from your provider, to speak in a way that your provider will understand.

For example, our weekly pregnancy moment is written by the midwife … that way, you get access to the midwifery philosophy, because we know evidence shows that interdisciplinary care where midwives and OBs are working together actually has good outcomes. [In] other developed countries, that’s what they use. The weekly pregnancy moment that’s written by the midwife includes how to communicate with your provider, how to navigate as a woman of color. You’re getting that weekly, “This is where you are. This is the kind of thing, because of who you are, that you need to be talking to your provider about. This is how you can have that conversation.”

[It’s about] giving moms, one, a space and a community where they feel validated and a space where they have the tools to communicate with their provider, to be able to talk to their provider and get the kind of outcomes that they want, and a friendly place where healthcare is not the scary thing, providers are not the scary things. There are people like us, who we can communicate with and take away that stress. Normalize that conversation that it really takes a village to have a healthy person and providers are not God. Having providers in our midst, that we can easily talk to, it’s one of the things that we hope to accomplish.

[We want to bring] community, prepping for the provider appointments, and … being able to demystify the myth of work being with the provider. You have access to providers and have culturally competent providers you can talk to.

It only empowers the moms to seek if there’s anything, a Wolomi mom has gone through, [one] that’s gone through Wolomi, we want them to know and find a trusted provider. We want … our main goal is that provider/mom relationship. If you can get … Supporting the mom to get the best provider that they’ll trust, because at the end of the day, that’s who’s making the life and death decisions.

The importance of community for new parents

The whole idea behind Wolomi is bringing that community to moms. What is the importance of having that community?

Pregnancy and postpartum journey, and honestly parenthood, is a very lonely place. I remember one time we were having a group session, and one of the sessions that was led by a therapist, and a mom really busted out crying. One of the things she said was, “I go all day being somebody else in the workplace trying to navigate that in the workplace, and I haven’t had the time to be in a space of people like me, where I could be myself and focus on me as a mom and pregnancy.”

Code switching. You’re code switching all day. There’s so much demand. There’s this thing, there’s stats out there that are saying that Black women are one of the highest business starters in the US right now. Imagine that, and a lot of them are not starting the business because their parents have started a business and are helping them, showing them the ropes or funding and all of that stuff. The stress of that, having to … there’s other stats saying 45% of women of color, which includes Black, Hispanic, and Southeast Asians in this research, 45% of them are more likely to want to leave the workplace compared to 30% of white moms — which is still bad, women in general, in this women burnout series that we are having. When you do the research, the layer, it’s even worse for women of color.

There’s another article that was saying, because they have to be somebody else at workplace, they can’t really truly be themselves. That’s why they become entrepreneurs, to be honest, because there’s a lot of stress in that — not wanting to fully be you because then you might not be what people want.

Creating that space and motherhood, the journey is such a precious time that you reflect on a lot of things. A lot of things come up. Having that space where you can, it’s okay. You could be you. I’ve seen that before, I’ve seen you before, it’s a reflection of me, and we want to create that. We are thinking seriously about how we create that for Black women, for Hispanic women, for Southeast Asian moms, anybody who feels “othered.” How do we create that space for them, where they feel that, “Okay, I don’t have to do this pregnancy alone. I have a place where I can be, and I could just be me so that I can reflect on what I need. I can get things that I need, I can prioritize what I need to be successful in this journey.”

That’s the importance of the community. That’s what’s hard about the healthcare system, right? When the moms are saying things, the receiver is not understanding it, maybe because it’s foreign to them, the way it’s articulated, the way it’s showing up. You could be in a place where you’re not foreign. You can think about what you want out of this journey.

The tools Wolomi is bringing to parents of color

What kind of resources does Wolomi offer to achieve all those goals?

We have the weekly pregnancy moment. When a mom downloads the app, when you download the app, you put your estimated due dates and you get the weekly pregnancy moment written by a midwife of color.

We have different events like the pregnancy circle, the feeding lounge. In the next few months, we’re starting our Hispanic postpartum circle. We have a Spanish speaker who is also a nurse and a lactation specialist who is in our community. I’m really very excited about that. We have that and we have “parenting like a boss.” We have different events that are short, that are easy, [where] moms can ask questions.

We have the community where they can free text and say whatever’s on their mind and get peer support, but that is also moderated by health experts. Unlike going on a search engine, you can find a trusted expert who can moderate the conversation, because we want you to have evidence, clinical evidence in the decision you’re making as you collect information.

I talked about the weekly moment. I talked about the events, the community, and then the “ask the experts.” The other layer that we have is we are soon, going into the fall, we are going to have our birth class. That’s going to be exciting. The moms can … It really teaches you how to have those conversations, what you need to do to take care of yourself during the post-pregnancy journey.

The other thing right now is our partnership with March of Dimes in the DC area. With that, we are able to support the moms who are peer advocates. That peer advocate not only helps them to navigate the platform [but also can] make sure you know where to go, how to ask questions, how to use the platform, [and] also, you get to create a goal. What goals do you have? That adds another layer of evidence-based intervention, which is peers, having your peers that can support you throughout your journey. That’s one thing that we’re doing with March of Dimes, and it’s getting good results and we are excited about that.

The Wolomi app

Tell us a little more about the companion app for Wolomi and what expecting and new moms can find in that app to help them on their journey.

The companion app is those four things, the weekly moment. You put your estimated due dates and every Sunday, you get this nice text or notification that tells you, “Hey, this week, this is what the midwife has to say.” You read it and it tells you what you should expect and really focus on what you should be discussing with your provider because we want that outcome, and what the change in your body is as a woman of color. At this stage, we’re really focused on the medical interaction, which is different from other weekly things that you get out there. This is more focused on how you navigate, how you talk to your healthcare system, how you get what you want from your healthcare system that week.

We [also] have the community. There’s a community in the app. You’re free to send any message you want, and then you’re able to chat with the experts. You can send … You pick an expert, you have the nutritionist there, we have OB, we have midwife, we have therapists. It’s for information and education. We’re not necessarily providing care, but a sounding board where you can think through things. That’s really the purpose of it. [As for] the events, you could save the events that we are going to have, and then you can join the events from the app.

When the mom downloads the app, there is a mental health screening that goes on. That’s part of the onboarding process. If the mom screens high, we definitely email them. If they’re part of any of our programs, for example, the March of Dimes program, or in a place where we have a partnership with the employer, or we have a partnership with the health plan, we’re then calling and making sure that you’re following through.

If you’re a mom that’s on the app, if you screen high, we do send an email to say, “Hey!” If we have a partnership and you’re in that, if you’re a member of the March of Dimes in the DC area … you download the app, you put the code in, and you’re going to get a call from us. You’re going to get a call from the peer advocate anyway, that’s going to tell you, “Hey, we want you to decide your options.”

I’m so excited that there’s a national hotline now for maternal mental health. That is great. That’s one of the things we are adding to the email that goes out if the mom screens high.

How the system can do better

How can the healthcare industry do better for women of color, especially mothers of color?

One of the things that we have to do is have different metrics in which we measure provider/patient relationship. Are we even measuring that? There’s a lot of work that’s been done in making sure that all these other things that add to better outcomes are being paid for.

We could do more. We could do more on a platform like mine. How is that? There’s no one size fits all. The health system needs to be open and listen to the different possibilities. The most important thing is listening to them, really.

I’m having the idea that, oftentimes I’m sitting in meetings where people, well-meaning people, are saying a lot of things. Well-meaning providers are saying a lot of things, but it’s like, “Okay, the death and the suffering is not happening with some random alien provider somewhere. We are the ones that are doing it. We have to realize that. It’s us. We should look in the mirror.” If you are a provider, there’s a possibility that your patient is feeling a certain way if they’re a patient of color and [you should] be okay with that — not in a don’t care way, but be okay with that when they come to you and say, “I’m scared. Am I going to die?” Be okay with that, don’t take offense, explore it. If you feel like, “Okay, I need to take more classes on something,” do it! If we don’t look in the mirror, we’ll always think that it’s somebody else.

Really, number one, we need to be tracking our data. If I’m a provider, I need to know what my data is looking like. What gets measured, gets solved, or whatever, gets better. If you don’t know what your data equity data is, you are going to think, “It’s that other doctor” … because how could you? You’re the best nice doctor ever? How could you be the one not listening to your patients? How could you be the one? Data doesn’t lie.

If you have the data, personal data, quarterly, you get a report. In order for us to do that, we have to take it seriously, and then be open about being okay with sharing with your patients the data. Be okay with sharing what you’re doing to do to get better, and then they will trust you. We have a long way to go, but that’s just one way to do it.

Download the FREE Wolomi app in the Apple App Store or Google Play Store and become a member of the community at no cost for a limited time. Join their tribe to connect with health experts and other women on their pregnancy journey.